In many ways we are traveling back in time.

I began this series in the modern City of Guelph Ontario with the discovery of a statue honoring John Galt.

I then discovered that novelist Ayn Rand had visit the area 60 years ago and that this John Galt was the inspiration for the name of her central character in the novel Atlas Shrugged.

Wanting to learn more about the real John Galt took me back to the early 19th Century and the discovery that the John Galt who founded Guelph held views that were almost the diametric opposite of those Rand had championed in her novel.

Among the ideas the real John Galt advocated was the then new philosophy of John Stuart Mills known as Utilitarianism.

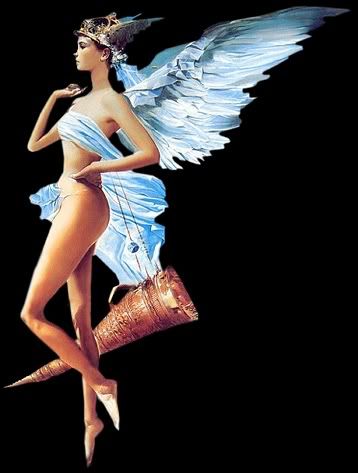

Now I want to go back even further in time and explore the connection between Utilitarianism and the most popular of all Roman gods, the goddess Fortuna.

Or "Lady Luck", as she's now known (and still worshiped) in Vegas.

Most people today have never heard of Fortuna. When they think of Rome they think of Jupiter or Mars or Venus, Rome's great gods of state. And certainly these were the gods the Romans officially worshiped, but they were not the god the Romans worshiped the most.

In terms of the amount of tribute, in terms of the number of shrines, the goddess uppermost in the minds of most Romans was the Goddess Fortuna.

The morality required by the worship of Fortuna will seem very strange to us today. Following a Judaeo-Christian tradition the rules of morality were literally cast in stone. Read the Ten Commandments and you know the will of God in advance of your behaviour. Not so with Fortuna, the goddess of good (and bad) fortune.

Let's take a mundane example. You are at an ATM withdrawing twenty dollars when the machine starts spitting out hundreds of twenties. The lobby of the bank fills with money. Morally what are you to do?

Today it would seem obvious. The money does not belong to you so the morally correct choice is to return it. Thou Shall Not Steal, is the expressed will of God.

But to the ancient Romans the proper moral choice would not have been so obvious. Fortuna was a fickle goddess. You could not know what the right and proper and moral action would have been until after you had acted. You would know it by the way Fortuna rewarded you for your behaviour.

If Fortuna did not want you to have the money and you kept it, you would be arrested and charged.

On the other hand if Fortuna wanted you to keep the money because she wanted to punish the Bank for its greed you would be performing a moral act and would get away with it, living long and certainly prospering. Keeping money that wasn't yours would have been a moral act sanctioned by the gods.

In Roman times no one knew what was morally correct until after taking action and suffering the consequences. It was the consequences Fortuna applied to the preceding actions that revealed their morality. Morality was a matter of interpreting Fortuna's shifting moods.

But what has this to do with John Galt?

Simply this, the ancient moral code of the goddess Fortuna was the inspiration for Mills philosophy of Utilitarianism. the belief that the moral worth of an action is solely determined by its contribution to overall utility, that is, its contribution to the happiness or pleasure of the greatest number of people. It is a form of consequentialism, meaning that the moral worth of an action is determined by its outcome—the ends justify the means.

This is Fortuna's moral code in modern guise, with this exception, that now Mills believed he had understood the mind of the goddess and knew her expectation.

It is a strange world we live in.

*****************************************************************

Images courtesy of Photobucket

The Snow Pile and More

15 hours ago